Why is reliability an issue?

Screw propellers became a mainstream ship propulsion system in the late 19th century. Screw propellers superseded many paddle wheeler ships, which were the predominant propulsion method for motor-driven ships. Since that time, screw propellers have been widely applied to fishing and pleasure boats, passenger and container ships, Very Large Cruise Oil Carrier (VLCC), etc.

Because of the long cruising distance, especially for large ships, reliability is essential for propellers and engines. Furthermore, the propeller’s working environment, i.e., under seawater, is very harsh. Therefore, manufacturing screw propellers require high levels of design and production technologies. Screw propellers with high performance need to meet the following criteria: strength, efficiency, and cavitation.

Cavitation refers to the phenomena where bubbles are generated in the water when the water pressure becomes lower than saturation pressure. When the propeller rotates at high speed, water velocity at the propeller’s tip becomes very high, and pressure becomes low as per Bernoulli’s principle. When the cavitation area increases on the blades’ surface, it causes lowered thrust, vibration, and noise. Furthermore, the energy released by collapsing bubbles causes erosion of the blades.

Challenge for design engineers

For design engineers, it is a challenge to find a design that achieves good performance due to tradeoffs between the three areas; strength, efficiency, and cavitation. For example, if priority is given only to efficiency, the screw blade needs to be thinner, resulting in insufficient strength or strong cavitation, which would damage the ship. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate performance in the three areas. For the investigation of strength, Finite Element Analysis (FEA) and material tests can be applied. Simultaneously, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and simulated experiments would be ideal for studying efficiency and cavitation.

CFD has been established as a tool to predict fluid flow, fluid-structure interaction, and more complex phenomena such as cavitation. Integrated flow parameters along a propeller surface are used to evaluate the propeller’s efficiency and used as input data for structural analysis as a load. It is also convenient and cost-effective to virtually tests many variants of the products and optimize the design.

When both fast and accurate are important

A design engineer interested in using CFD to work on propeller design has unique needs that require a unique product. As the primary task of a design engineer designs, the CFD software used for simulation needs to be easy-to-use, powerful to handle complex (and dirty) models, accurate, and fast to keep up with the design process’s speed. And perhaps most importantly, it needs to be embedded in CAD.

Simcenter FLOEFD is a CFD tool embedded into Siemens NX, Solid Edge, CATIA V5 and Creo. It is an ideal tool for design engineers because they can conduct CFD analysis inside their preferred CAD environment without learning a new user interface. Simcenter FLOEFD is highly automated, and thanks to its unique SmartCellsTM technology, design engineers can easily perform CFD simulations without simplifying the geometry. It is fast and still highly accurate to keep up with the fast-moving design environment. Let’s take a look at an example.

Potsdam Propeller Simulation Test Case

We used the Potsdam Propeller Test Case (PPTC) benchmark test case.

The data related to the benchmark test case was published by Schiffbau-Versuchsanstalt Potsdam GmbH (SVA) to test and validate simulation methodologies. A significant portion of the work undertaken by the SVA relates to research projects. With its three departments, Resistance and Propulsion, Propellers and Cavitation, and Maneuvering and Waves, the SVA covers the entire spectrum of modern shipbuilding testing practice.

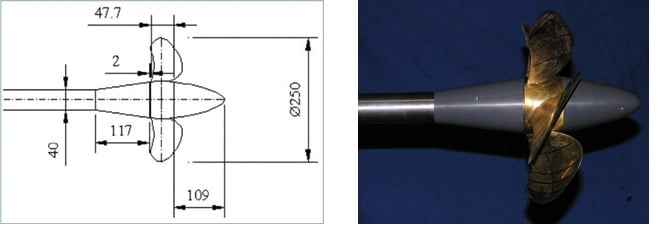

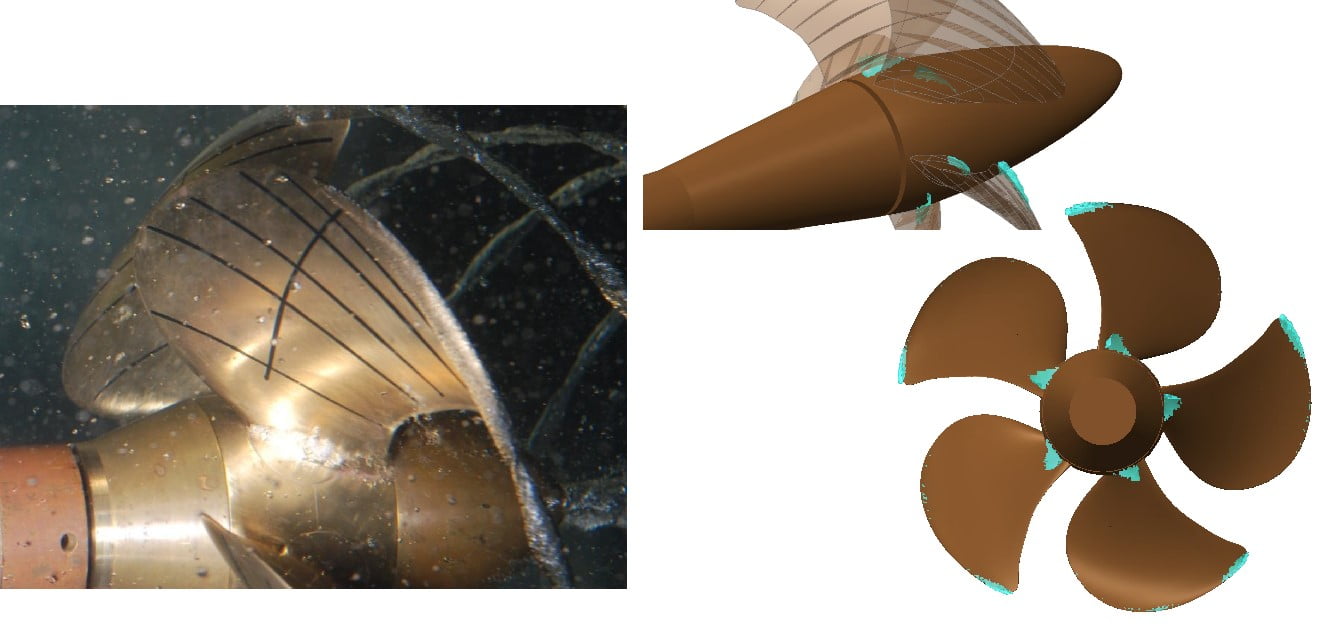

The propeller VP1304 was used for the benchmark test. VP1304, designed to generate a tip vortex, is a controllable pitch propeller with a right-handed rotation direction.

| Diameter | D = 0.25 m |

| Pitch ratio r/R = 0.7 | P0.7/D = 1.635 |

| Area ratio | AE/A0 = 0.77896 |

| Chord length r/R = 0.7 | c0.7 = 0.10417 m |

| Skew | θEXT = 18.837° |

| Hub ratio | dh/D = 0.3 |

| Number of blades | Z = 5 |

| Sense of rotation | right |

Simulation model

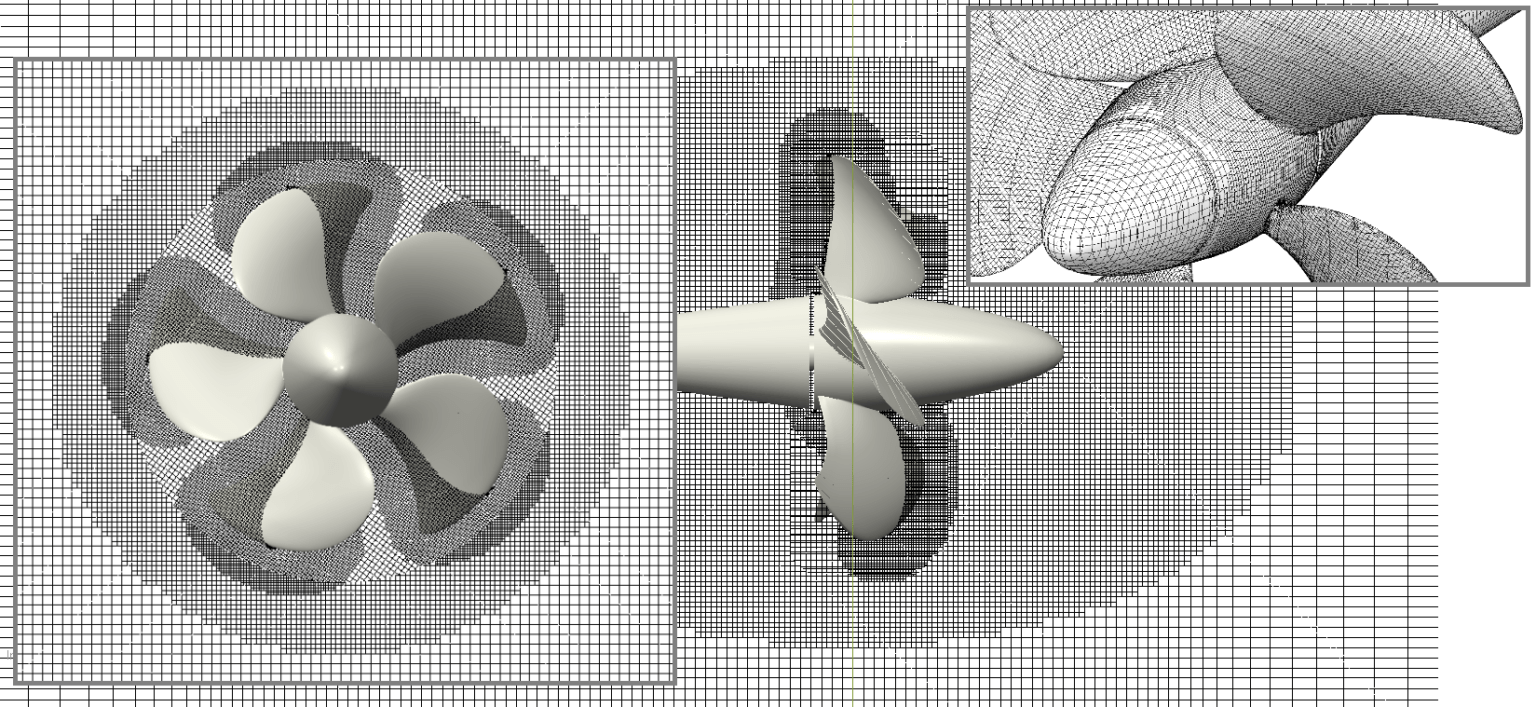

In the simulation for the open water test, two geometric scales of the model are considered: a scaled model with a scale of 12 and a full model. For these two cases, water properties slightly differ from each other, and the rate of revolutions for the scaled model is 15 1/s and for the full model is 4.33 1/s. The simulations for five advance coefficients J = 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4 are compared with the experimental data. For this comparison, thrust coefficient (KT), torque coefficient (KQ), and open water efficiency (η0) are considered. The mesh in Simcenter FLOEFD was created as a uniform rectangular dominant mesh with a high mesh density in the vicinity of the blades and extended in the direction to boundaries of the computational domain with some ratio. Thanks to Simcenter FLOEFD’s unique SmartCellsTM technology[SN1], it is unnecessary to resolve boundary layer by mesh. The total mesh size for this task is 6 million cells (Figure 3).

Figure3: Mesh around propeller with local mesh refinement

Figure3: Mesh around propeller with local mesh refinementThe calculations were conducted in the transient regime using the “Sliding” mesh technology to simulate the propeller rotation. The scaled model’s time step is 0.0024 s, and for the full model – 0.0083 s.

| Task | Time [min] |

| Model preparation/Repair | 0 |

| Physics model setup | 10 |

| Mesh setup/Grid generation | 30 (partially computer time) |

| Solving | 350 per case (10 jobs in parallel) |

| Post-Processing | 240 |

| Total human invest | 280 (4.5 h) |

| Total time (human + solver) | 630 (10.5 h) |

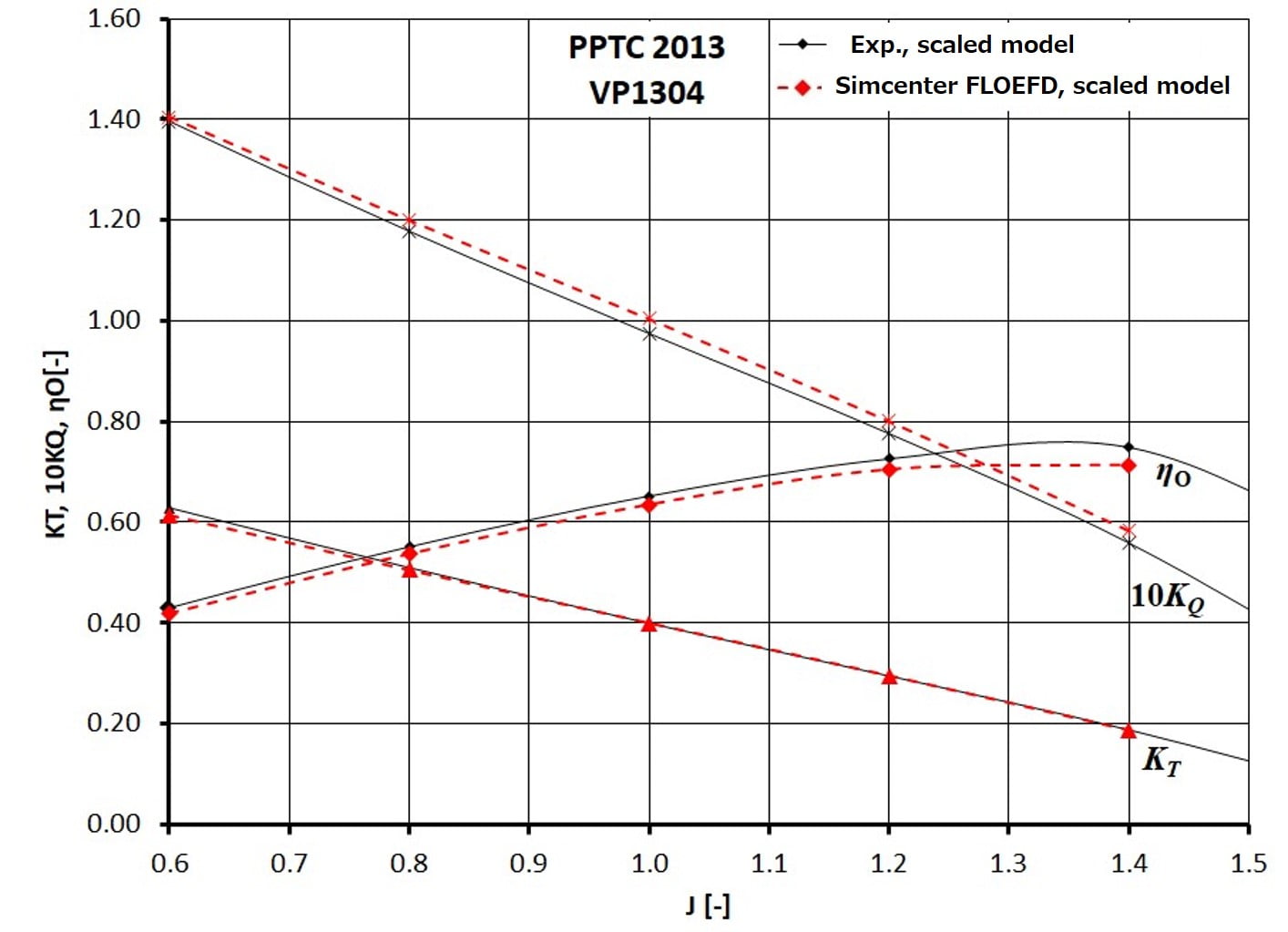

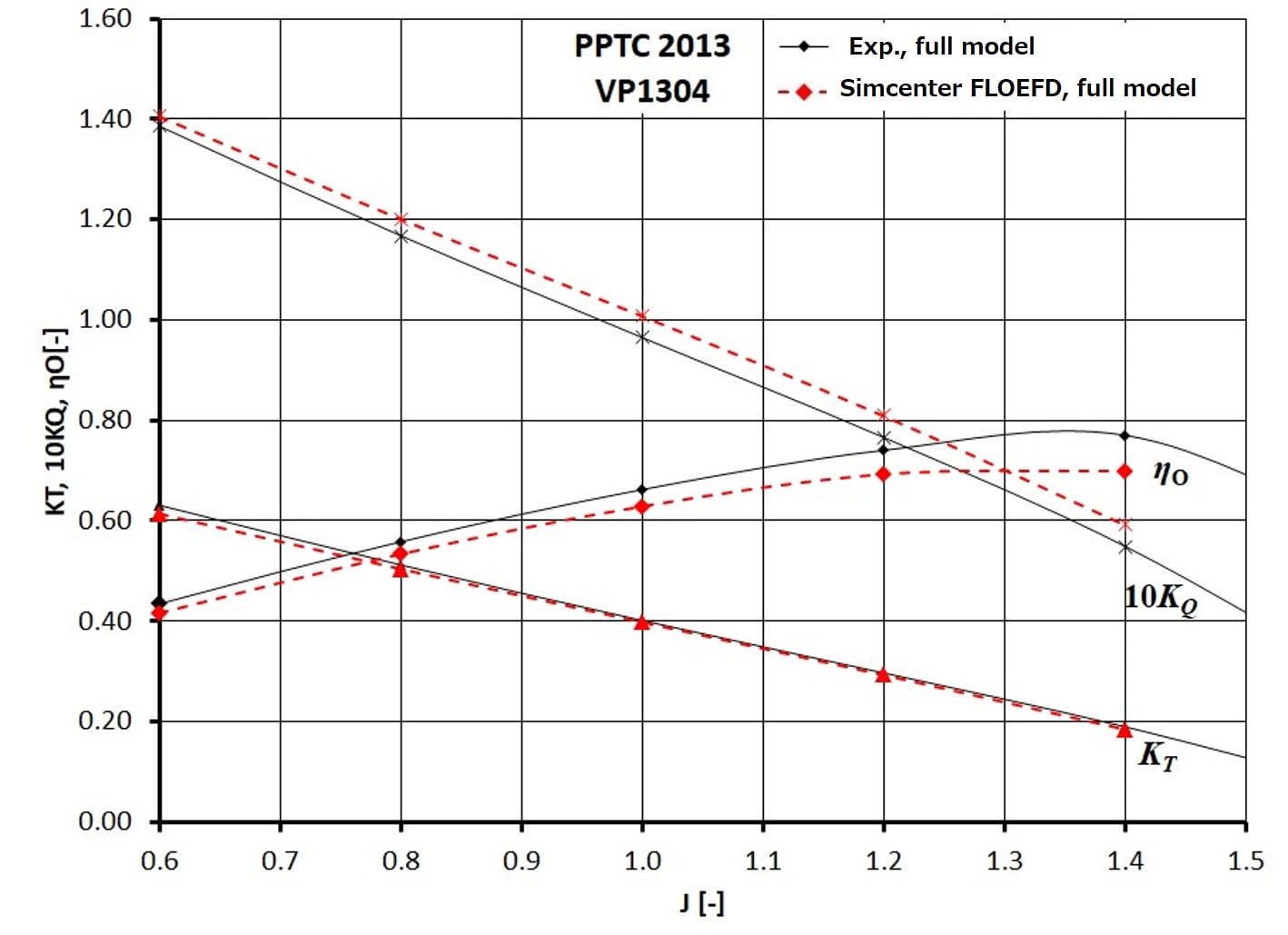

The propeller performance is usually represented using non-dimensional coefficients like thrust and torque coefficients and open water efficiency. Comparing the simulation results and experimental data in terms of these coefficients is shown in Figures 4 and 5. These graphs show good agreement between Simcenter FLOEFD data and measurements with relative errors weighted overall advance coefficients for the scaled model of 0.62 % for KT, 2.65 % for KQ, and 3.18 % for η0. For the full model, these errors are 1.69 % for KT, 4.46 % for KQ, and 5.86 % for η0. All data show that KT and KQ decreasing with J’s increase, and η0 achieves maximum at J = 1.4.

Figure4: The open water characteristics of the scaled propeller model.

Figure4: The open water characteristics of the scaled propeller model. Figure5: The open water characteristics of the full propeller model.

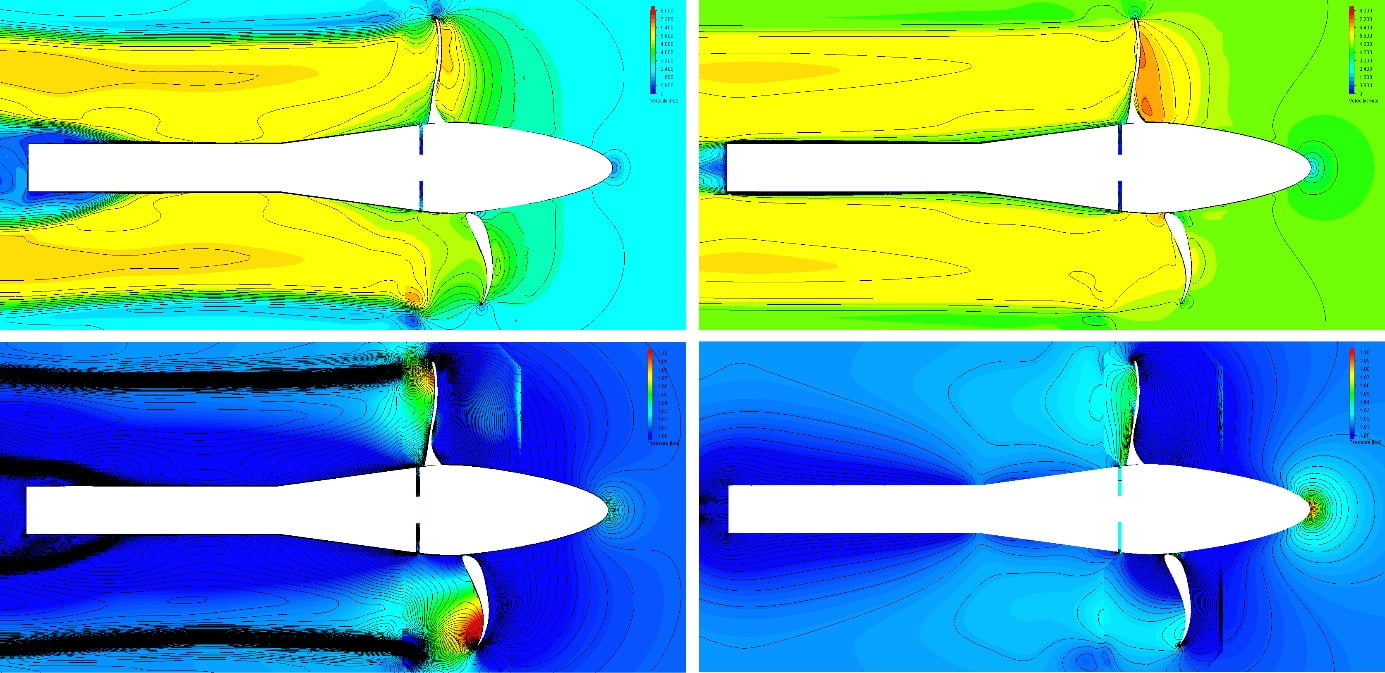

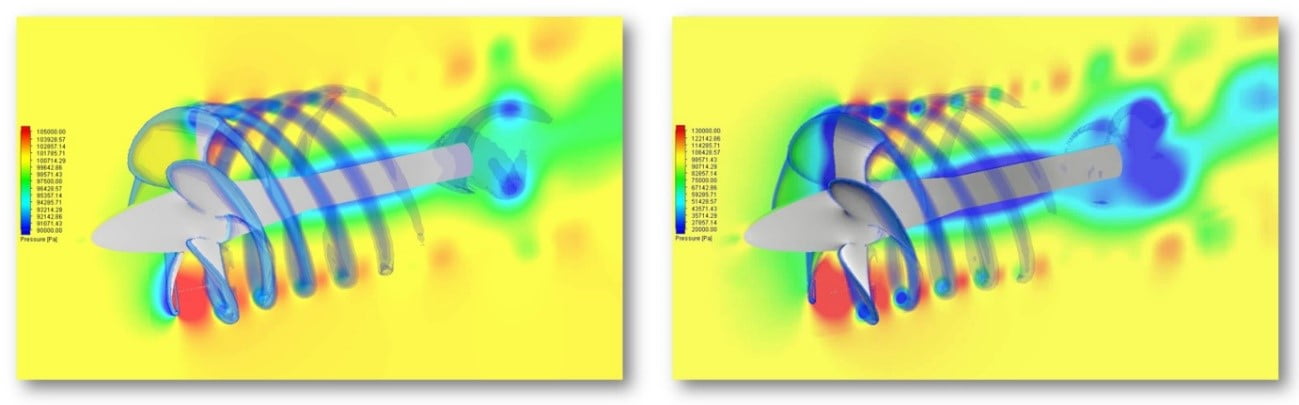

Figure5: The open water characteristics of the full propeller model.The following pictures show velocity and pressure distribution around the propeller for J = 0.6 and 1.2 at the center cross-section in the side and front planes for the scaled model (Figures 6, 7).

Figure6: Velocity (top) and pressure (bottom) distributions at J = 0.6 (left) and J=1.2 (right) for the scaled model at the central cross section in the side plane.

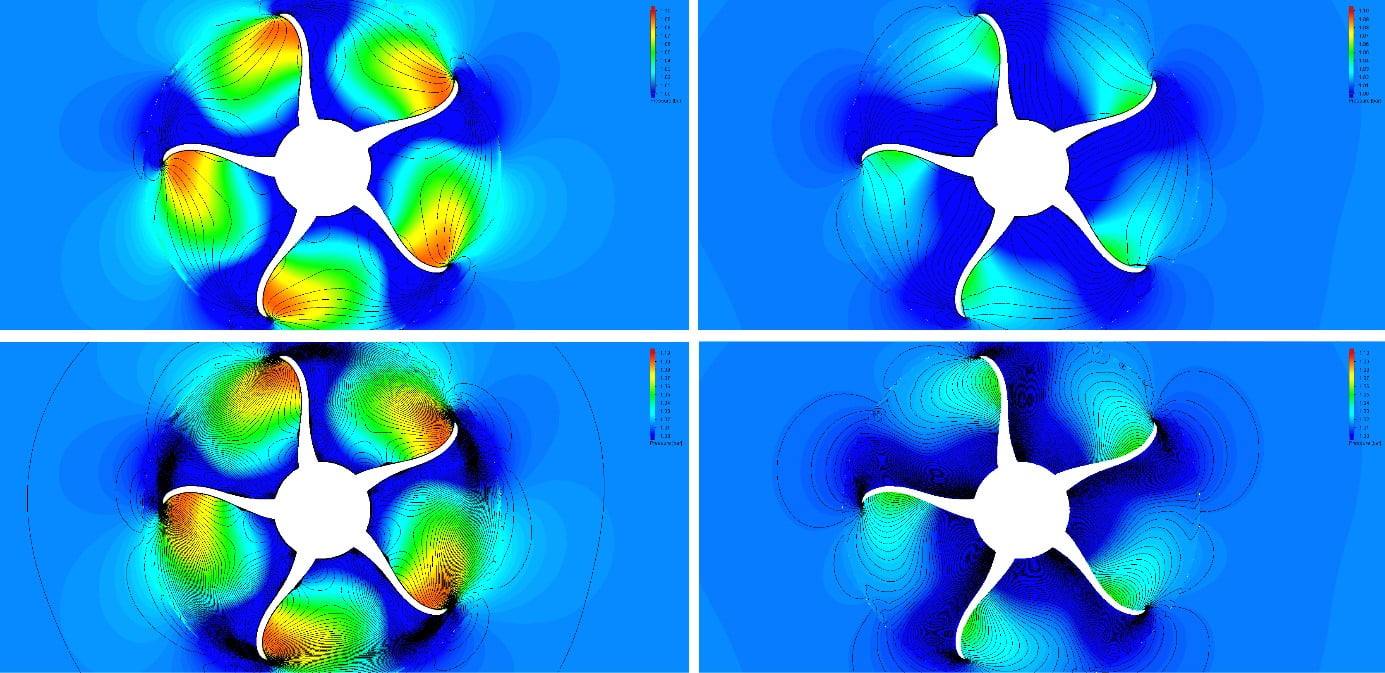

Figure6: Velocity (top) and pressure (bottom) distributions at J = 0.6 (left) and J=1.2 (right) for the scaled model at the central cross section in the side plane. Figure7: Velocity (top) and pressure (bottom) distributions at J = 0.6 (left) and J=1.2 (right) for the scaled model at the central cross section in the front plane.

Figure7: Velocity (top) and pressure (bottom) distributions at J = 0.6 (left) and J=1.2 (right) for the scaled model at the central cross section in the front plane.Figure 8 shows pressure distribution at the central cross-section and iso-surfaces of vorticity for the scaled (angular velocity is 15 1/s) and the full (angular velocity is 4.33 1/s) models.

Figure 8: Pressure distribution at the central cross-section and iso-surfaces of vorticity for the scaled (left) and the full (right) models.

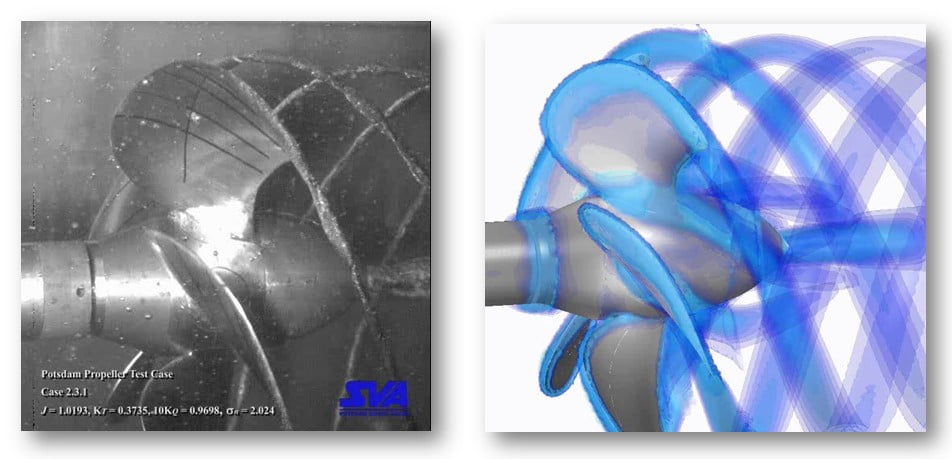

Figure 8: Pressure distribution at the central cross-section and iso-surfaces of vorticity for the scaled (left) and the full (right) models.SVA also published experimental data of the cavitation regime for the scaled model in terms of thrust coefficient. Simcenter FLOEFD results of this complicated phenomena were compared with the measurements. The case with J = 1.019 and cavitation number (σn) = 2.024 is considered. For this test, the rate of revolutions is 24.987 1/s.

The comparison between Simcenter FLOEFD predictions and experimental data are shown in Table 5, Figures 9, and 10. It should be noted that they are comparable.

Figure 9: Cavitation observation in the experiment (left) and iso-surfaces for vapor volume with a value of 20% in Simcenter FLOEFD (right).

Figure 9: Cavitation observation in the experiment (left) and iso-surfaces for vapor volume with a value of 20% in Simcenter FLOEFD (right).| J | σn | KT | |

| Simcenter FLOEFD | 1.019 | 2.024 | 0.3703 |

| Experiment | 1.019 | 2.024 | 0.3725 |

| Error, % | – | – | 0.6 |

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates Simcenter FLOEFD to solve these kinds of applications for marine propellers and find characteristics for the open water tests and cavitation regimes. The ability to conduct these types of studies within their preferable CAD system is a great benefit for design engineers who want to optimize the propeller performance during the early design stages.